On February 03, 1801 in Celtic History

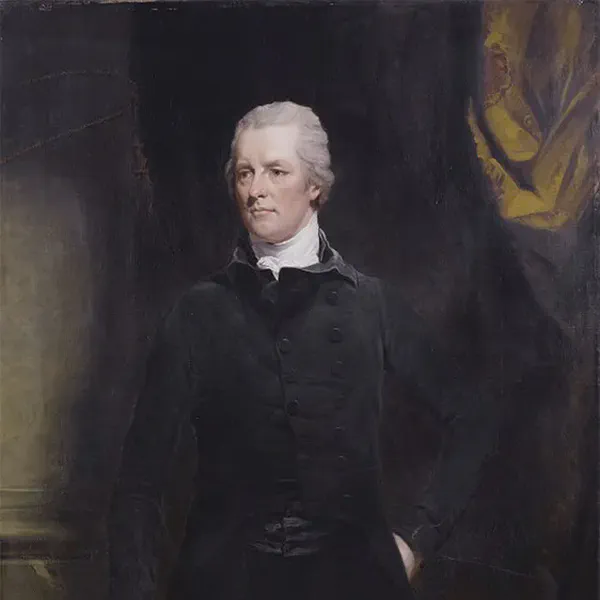

Prime minister william pitt resigns over royal veto on catholic emancipation

William Pitt the Younger, who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, did tender his resignation in 1801, in part due to the issue of Catholic emancipation and a related royal veto. Pitt, in office from 1783 to 1801 and then again from 1804 until his death in 1806, was a prominent political figure whose tenure was marked by major events including the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

The issue at the heart of Pitt’s resignation was the Act of Union 1800, which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, effective January 1, 1801. A key aspect of Pitt’s support for the Union was his intention to follow it with measures that would grant Catholics in Ireland greater rights, including the right to sit in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This policy was known as Catholic emancipation and was intended to integrate the Catholic majority of Ireland more fully into the political life of the newly formed United Kingdom, addressing longstanding grievances and inequalities.

However, King George III opposed these measures, believing that to agree to Catholic emancipation would violate his coronation oath to maintain the Protestant religion. The King’s strong opposition and the resulting political crisis led Pitt to resign, as he felt he could not carry out his policy without the King’s support. Pitt’s resignation was a significant moment in British political history, highlighting the tensions between the executive government and the monarchy, as well as the complexities of integrating Ireland into the United Kingdom.

Pitt’s concern for the union with Ireland and his resignation over the failure to achieve Catholic emancipation illustrate the challenges of governing the diverse and often divided societies within the British Isles. Catholic emancipation itself would not be achieved until 1829, under the premiership of the Duke of Wellington, illustrating the protracted nature of this political and social issue.

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws. Requirements to abjure (renounce) the temporal and spiritual authority of the pope and transubstantiation placed major burdens on Roman Catholics.

The issue of greater political emancipation was considered in 1800 at the time of the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland: it was not included in the text of the Act because this would have led to greater Irish Protestant opposition to the Union. Non-conformists also suffered from discrimination at this time.

William Pitt the Younger, the Prime Minister, had promised emancipation to accompany the Act. No further steps were taken at that stage, however, in part because of the belief of King George III that it would violate his Coronation Oath. Pitt resigned when the King’s opposition became known, as he was unable to fulfil his pledge. Catholic emancipation then became a debating point rather than a major political issue.

The increasing number of Irish Catholics serving in the British army led to the army giving freedom of worship to Catholic soldiers in 1811. Their contribution in the Napoleonic Wars may have contributed to the support of Wellington (himself Irish-born, though Protestant) for emancipation.

More From This Day

Harry Boland and Michael Collins engineer Eamon de Valeras escape from Lincoln Jail in England

February 03, 1919

Lady Jane Wilde (Spiranza), poet, nationalist and the mother of Oscar, dies in London

February 03, 1896

Irish Land League organizer Michael Davitt is arrested again in Dublin

February 03, 1881

Lord Netterville, indicted for the murder of Michael Walsh, is acquitted by his Parlimentary Peers

February 03, 1744